Thought Sorter

Your brain is incredibly busy. There are always far more things you could be thinking about than you can manage to hold on to and process. In addition there are all those things that you are not consciously thinking about, but that your brain is taking care of anyway without your awareness (like keeping you balanced as you walk, regulating your body, reading this text, or remembering your sister’s birthday). How does it manage to do all this, and how do you decided which jobs you need to consciously bother with?

Level 0: Simple Conscious Thoughts

Nothing Comes for Free

Practise Makes Lazy

- our automatic, learned processing of tasks are much faster than the conscious, deliberate way of thinking;

- the background processing also uses much less energy.

Level1: Simple Thoughts, Processed Unconsciously

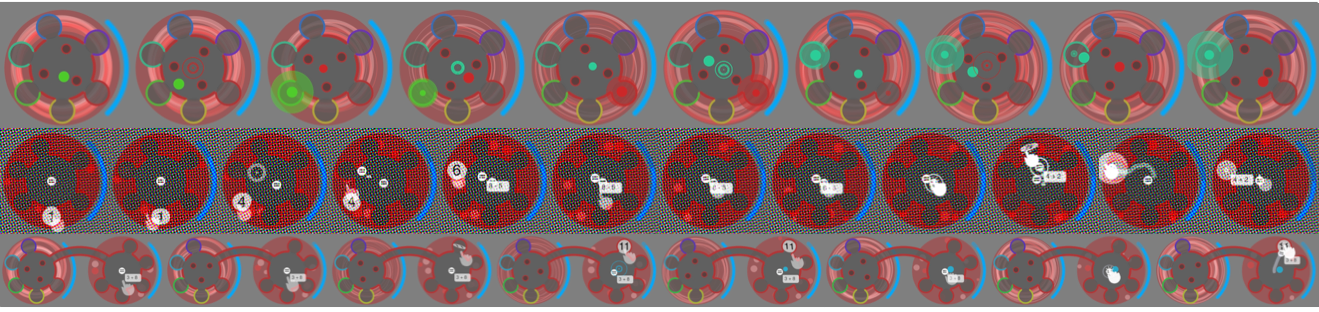

Take a look at this illustration, where our mind has learned the tasks of sorting coloured thoughts without the need for conscious involvement. Note that it handles more thoughts more quickly that you could keep up with , and energy is used at a much slower rate.

Level 2: Trickier Thoughts

Cognitive load

Level3: Two Minds for Two Problems

So now we can combine the two types of problem and have a mind of two halves. An automatic mind that is really good at sorting coloured thoughts, and a conscious part (that’s you) that can handle number sorting. In addition, since all the thoughts are coming into our conscious mind to start with, we have to send the coloured thoughts over to the auto mind for processing (kind of like we are outsourcing these tiresome simple tasks to some lower powered, but faster, slave mind).

Level 4: Even Tougher Thoughts

This is quite a bit harder, slower and more expensive. You can probably feel how much slower this is. You have to really concentrate on both the result from the simple maths problem, and remember where the numbered buckets are. The cognitive load is much higher.

Level5: Two Minds for Three Problems

Now you may be spotting a flaw here. Brains are good at spotting patterns and efficiently processing known problems, while our conscious mind is slow and expensive. So why are all the problems coming to us first for us to slowly and at great expense, sift and sort them. What if part of our faster, less able brain could decide if it can handle coloured thoughts on its own. It doesn’t have to solve them, just recognise the type of problems and send it on for either simple, automatic processing, or on to the conscious mind that can handle it. This is still just a pattern recognition problem, which our unconscious brain is pretty good at. Only the trickier problems get passed on to you, the conscious mind, for slow, expensive processing.

Level6: The Optimal Mind?

Lets see what that would look like.

Summary

Exploring the Idea Further

Here I take a deeper look at some of the ideas explored in the Thought Sorter game levels

Total, Singular Focus

Overwhelming Awareness

This Just Cannot be Right

Another Possibility

Multiple Minds - Nothing New

Who is the Boss?

Learn Through Play

Related Thoughts

Lazy? Or Just Efficient?

When you have some task, for which the only solution is sustained, focused, mental effort, you may find you mind wandering onto other, more well rehearsed or habitual activities. Your mind can convince itself that perhaps some other task is a better use of your resources – busy work. Procrastination might feel like a kind of conscious laziness, but it is actually the result of your brain’s gatekeeper doing it’s job well – deciding what tasks really need conscious awareness, and batting away those that exceed current capacity.

Left to its own devices, this gatekeeper doesn’t really care how valuable your current conscious effort is, in terms of your personal goals and motivations. It’s job is just to allocate and preserve precious resources. We are straying into the world of attention and decision making here, which is too big a topic that we will definitely revisit another time. For now understand that your brain will often lead you to some time-filling tasks that demands less of your conscious, fully engaged mode of thought, and will help you get occupied in a simple activity – maybe a game, or watching a TV show, or scrolling a social feed – these activities will occupy your conscious capacity (so you don’t look around for something useful to do) but they mostly require little highly focused skill or problem solving that is so expensive to run.

When you hear the phrase “pay attention” just stop and think that to the brain, there is a real cost to full attention – so give the brain something truly worthwhile to spend it on.

Sleight of Mind

Our tendency to focus on just what we need to, while filtering out what seems to need less attention, gets exploited by performers, actors, and magicians. These tricks can also be used in advertising and storytelling to keep our conscious attention on something demanding in the foreground, while being unconcerned about peripheral distractions.

There are a couple of famous psychology experiments that look at this selective attention phenomenon. Both of these are reproductions of studies carried out by Daniel Simons, a psychology professor who specialises in visual perception, awareness and attention.

Credits

Other Experiences

- Imagine if you did not have any filter on your awareness; that in order to decide what to bother yourself with, you had to be aware of everything, all the time. And then in the next moment, you have to do that all over again. It would be distressing and distracting, making it hard to perform common tasks easily. Some people do experience the world like this – maybe not total awareness of background events, but certainly a much more conscious awareness of many demands that the rest can filter out. This can make life very difficult, and lead to other mental conditions brought on by the trauma and friction of living a life this way, in a world designed for those with a working filter.

- Conversely, imagine if you have no awareness, you do nothing consciously, and nothing stimulates you, and you have only your internal background tasks to occupy you. Boredom, despair, lack of mental growth are likely to occur. Animals that are kept in small, unstimulating environments have been shown to have reduced mental capacity and brain development. Similar results have been observed in groups of human orphans, kept in basic institutions for years. It is no accident that lack of stimulation for long periods is sometimes used as a form of punishment for people.

- You may find you are very good at focus, easily able to filter out trivial demands. If we focus exclusively on front-of-house focus work, and dampen some of the background distractions, it may feel like good for work productivity and problem solving, but the wrong balance can be damaging, and can lead to difficulties in relationships, and neglect in other areas of our life.

-

Our subconscious does not think too hard about what it is doing or why, other than to meet immediate drives and needs. It will do things that it knows how to do, repeating patterns of behaviour, and doing what seems important based on cues, eg. time of day, signals from our body, things happening around us, and – this is the important one – our basic priorities and drives.If we have beliefs and expectations that our situation is bad, that we are bad people, that we are somehow undeserving, the subconscious will make decisions and prioritise things, notice things that correspond to that and provide us with reinforcement of those beliefs. If you believe things are OK, or you have really important goal you are working to, it can help you achieve that too. These biased mental states and beliefs about ourselves can be powerful and they can be manipulated by others (controlling partners or bullies, unscrupulous advertisers, product designeres or media editors). But we also have some ability to modify these beliefs using techniques like Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT).This may sounds easy, but it’s not a switch. You have to really believe (or learn not to believe) a certain internal story, which can be hard in the face of external messages and existing beliefs. It takes practice, and when you are low already it can seem impossible.